This is the first of a series of blogs on udder health. This blog serves as an introduction, later blogs will cover practical information and solutions that you as a vet can provide to your dairy farmers. As an introduction, here are five important points they should understand.

1. Curing mastitis requires focus, structure and patience.

Mastitis is an inflammatory reaction of the udder tissue, and is almost always caused by a bacterial infection. Mastitis pathogens invade the udder and interact with the mammary epithelial cells. These cells release pro-inflammatory factors, triggering a local inflammatory reaction, causing swelling and pyrexia. Milk-secreting tissue and milk ducts throughout the gland are damaged due to toxins released by the bacteria, resulting in reduced milk yield and quality. All of this is very painful to the cow.

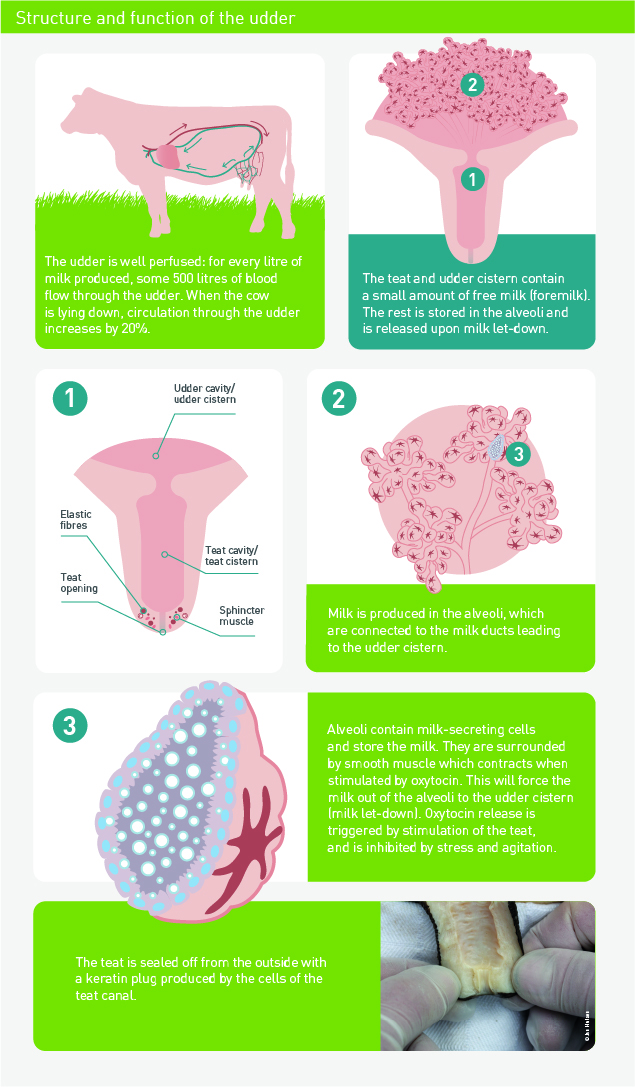

The udder is a sponge-like tissue, consisting of large trees of ducts ending up in bulbs, alveoli, formed by epithelial (milk-producing) cells. This can be compared to a bunch of grapes: the grapes are the alveoli, the walls of the grapes are the epithelial cells, and the stems are the ducts. Imagine millions of those together and you have a small piece of udder tissue.

In a case of mastitis, a part of the udder is swollen due an immune reaction. As a result, many of the milk ducts will collapse and be squeezed shut, trapping milk and inflammatory fluids (exudate) inside the udder.

An udder with mastitis has sponge-like swollen tissue full of bacteria and exudate.

The mastitis-causing bacteria are mostly located in the alveoli, and are shielded from attack by the white blood cells that are required to fight the infection and stop the clinical mastitis.

For recovery and healing it is essential to milk out the affected udder tissue. This flushes away bacteria, white blood cells and debris, such as mastitis clots. It also stimulates the blood flow both to and from the mastitis area, bringing in fresh supplies of oxygen, white blood cells and nutrients, and carrying out waste products and substances.

Antibiotics will support the white blood cells in disposing of the mastitis bacteria. But antibiotics are only effective if they reach the site of action – and if the bacteria are sensitive to that specific antibiotic.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) will reduce swelling and pain, and thus strongly support the recovery process. The immune system often overreacts, which can lead to tissue damage – and NSAIDs will lessen that risk. NSAIDs support both the udder tissue and the cow by helping her return to normal function. Pain relief plays a substantial role in this.

These notions are important when setting up a farm treatment protocol against mastitis.

- Setting up an effective mastitis treatment plan go to Mastitis in dairy cows | AHDB

After the bacteria have been successfully eliminated, it can take several days before the swelling has disappeared and the milk has returned to normal.

An udder that has had clinical mastitis, is at increased risk of another case at a later stage. This can be due to scar tissue or bacteria that remain in the udder. Or simply because this specific udder or cow is just more vulnerable to mastitis.

2. Mastitis bacteria enter the udder via the teat canal

The cow’s udder is made up of four independent glands (quarters) without interconnection: milk and bacteria cannot go from one quarter to another.

Each udder gland is built up of sponge-like tissue, that consists of large ‘trees’ of ducts ending up in pockets or alveoli, formed by milk producing cells.

The upper side of the udder mostly consists of glandular tissue, towards the teat the ducts join up into bigger canals, which form cisterns. The cisterns end up in the teat.

In between milkings, the milk is stored in the alveoli, with a small proportion of milk in the canals and cisterns.

- See The three pillars of successful milking

The only way for bacteria to enter the udder is through the teat canal. In between milkings, the function of the teat canal is to keep milk in and bacteria out. During milking, it should let the milk flow through, in a large volume per second.

The opening and closure of the teat canal is regulated by muscular and elastic fibres that surround it like a sphincter. The surface cells of the teat canal produce keratin, which also has anti-bacterial properties. After milking, the teat canal needs some time to close properly, and teat dipping will help in reducing udder infections.

- Find out more about good milking routines in The three pillars of successful milking

Incorrect functioning of the milking machine can lead to severe negative pressure on the teat end, and cause callus formation and loss of elasticity of the tissues in the teat end. Damaged teat ends stand a higher risk for udder infections, both in milking cows and in dry cows.

Here’s how to score teat ends and what the lesions mean

The small red stars are smooth muscle cells. Oxytocin causes these cells to contract, forcing the milk out of the alveoli towards the udder cistern and teat. This is called milk let-down. Stimulation of the teat and teat end induces an oxytocin release into the bloodstream. Agitation or stress inhibits this process, underlining the importance of quiet, calm milkers, and calm cows before, during and after being milked.

- Coming up: A guide to stress-free handling

The teat canal and its sphincter are designed to keep bacteria out, and they usually do. But if the teat canal is not sealed, bacteria can enter the udder, for example during and after milking and at the start and end of the dry period.

Most of these bacteria are flushed out again during milking or are quietly dealt with by the immune cells in the udder. But if the immune response is too weak or the bacteria too strong or numerous, inflammation will occur.

During clinical mastitis, the milk canals can become blocked by flakes or clots of milk and by swelling of udder tissue. An infectious agent colonising the upper part of the udder can be difficult to reach! NSAIDS will help and in some circumstances an oxytocin injection may be beneficial.

- Setting up an effective mastitis treatment plan go to Mastitis in dairy cows | AHDB

3. Know your enemy: identifying the agent allows targeted treatment and prevention

In virtually all cases of clinical and subclinical mastitis caused by bacteria, the pathogen has entered the teat via the teat canal.

The mastitis-causing bacteria can be divided into two groups: contagious bacteria and environmental bacteria. This division helps in deciding what measures are most effective to reduce and prevent infections.

The contagious bacteria live on the skin of the cow and sometimes in the udder itself. They spread from the udder of one cow to the udder of another cow. This primarily happens during milking. So good milking hygiene and optimal milking procedures are essential for prevention.

Contagious infections are sometimes called milk-borne infections. Also flies can transport these bacteria and bring them to the entrance (orifice) of the teat canal.

- See the three pillars of successful milking

The environmental bacteria live in the environment of the cow. In most cases, cows get infected from the bedding of their resting areas, and from the dirt on the floors and walkways.

Hygiene score: measuring the infection pressure

- Use the hygiene score card in VetIMPRESS/Multi Data/Cleanliness or from AHDB at https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/cleanliness-scorecard

Other origins such as contaminated teat dips, intramammary infusions, water used for udder preparation before milking, water ponds and mud holes have also been incriminated as incidental sources of infection.

Environmental bacteria:

Examples: Streptococcus uberis, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, coagulase-negative Staphylococci, coliforms (E. coli, Klebsiella)

Contagious bacteria:

Examples: Streptococcus agalactiae, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma

This grouping allows targeted treatment and prevention measures, once the bacteria that has infected the udder is identified, based on bacteriological analysis of a milk sample.

Laboratory testing of milk samples from affected quarters is the only reliable method to determine the pathogen involved.

- Milk samples: the key to mastitis control

- Taking a milk sample correctly – https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/aseptic-milk-sampling

4. Cell count is an indicator of udder infection

Milk somatic cell count (SCC) stands for the number of cells per ml of milk. Cells in milk include those shed from the inner surfaces of the udder as well as white blood cells as part of the immune defence. In a healthy udder the cell count is well below 100,000 cells/ml, probably around 50,000/ml or less.

As soon as an udder becomes infected, the immune system of the cow reacts by sending white blood cells into the udder and into the milk, causing the cell count to go up. In mild infections, the cell count will only go up one or a few hundred thousand cells per ml. In severe cases, the cell count can reach 1 million or more.

A small rise of cell count indicates there is an active immune reaction caused by bacteria that have invaded the udder. This rise in cell count is accompanied by a drop in milk production. Reducing the cell count will raise milk production.

The higher the SCC in a herd bulk tank, the higher the prevalence of infection in the herd. The loss of milk yield due to inflammation and tissue damage is directly proportional to the individual cow SCC: as SCC rises, milk production decreases.

One of the ways to detect a high cell count is using the California Mastitis Test (CMT) on milk samples.

- When and how should a CMT be used, and what does the result mean?

Subclinical mastitis: the invisible enemy

By definition, subclinical mastitis is without visible signs of local inflammation or systemic involvement. Cows are identified having subclinical mastitis via cell count.

The threshold varies between parities, and between countries and systems. Cows generally are identified as having intramammary infection (IMI) with a whole milk cell count of over:

– in first lactation (parity 1): 100-150,000 cells/ml;

– second and higher lactation (parity 2+): 150-250,000 cells/ml.

Once established, subclinical mastitis can become chronic and persist for entire lactations or the life of the cow, depending on the causative pathogen.

All dairy herds have cows with subclinical mastitis, although prevalence of infected cows varies from 5%–75% and quarters from 2%–40%[1].

Often, the bulk milk tank somatic cell count divided by 10,000 equals the approximate percentage of cows with subclinical mastitis in the herd.

Control of subclinical mastitis requires monitoring of bulk milk tank somatic cell count and cell count of individual cows on a regular basis.

- ⇨ Setting up an effective mastitis treatment plan: Mastitis in dairy cows | AHDB

Each case of mastitis gives any farmer a headache. First of all because unexpectedly, a cow has become sick with a painful disease, and farmers want their cows to be healthy. Secondly because of the risk that this cow can infect other cows. Thirdly because of all the work involved in treating and caring for the cow, including ensuring that her milk is separated from the milk of the rest of the cows and disposed of. On top of this, there are the financial costs…

5. Mastitis is a costly disease!

The overall cost of clinical mastitis is a sum of the following expenses:

- Production loss from damaged udder tissue is often underestimated, and is considered an indirect cost. Clinical mastitis causes severe damage to the epithelial tissue, reducing yield for the rest of lactation. After a case of mastitis, milk yield never returns to the earlier level. This cost is often underestimated and represents some 28% of the total cost of mastitis[2]

- Premature culling due to chronic mastitis is also an indirect cost. It is calculated as the difference between the sale and the replacement value and the cost associated with difference in yield of the replacement animals should also be added. This represents an estimated 41% of the total cost of mastitis.

- Labour. Mastitis cases take time to treat and slows down milking. A cow with mastitis should be milked separately or is housed in a sick cow group. Care of the cow can involve treatment, completing treatment records, milk discarding and tests to check that milk is free from residues. In severe cases, animals may need to be nursed and stripped out frequently, and are significantly more labour-intensive.

- Death. In severe cases, such as toxic E. coli mastitis, the cow can die. The total cost of a death is much greater than the value of the animal that has died. It will also include any treatments, time spent looking after the animal, disposal costs, a loss of genetic potential and the total loss of production.

- Treatment Therapeutics can include intramammary antibiotic tubes and other medicines such as NSAIDs, injectable antibiotics, oxytocin and supportive therapy such as an oral or IV electrolyte solution.

- Discarded milk. The cost of discarded milk is easy to calculate: add the treatment time to the milk withdrawal period and multiply by the average yield of the cow.

- Veterinary service. Veterinarians can be called to advise on the most appropriate treatment. Cows with toxic mastitis will require far more veterinary input than cows with mild mastitis.

- Diagnostics Mastitis often requires sampling for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing in order to determine the pathogen and the appropriate treatment.

Subclinical mastitis is costly, too!

Even if the cow’s health is not affected, it does have an impact on the quantity and quality of the milk. Costs of subclinical mastitis include:

- Reduced milk yield. There is a loss of milk production as subclinical mastitis damages the udder tissue. For every 100,000 cells above a SCC of 200,000 cells/ml, there is an estimated 2.5% loss of production. For example, yield of cows with chronic Staph. aureus can be reduced by 15% to 20%.

- Lower milk price. Depending on the milk contract, herds supplying milk with a high SCC can be penalised.

- Increased treatment. Cases of subclinical mastitis can become clinical, requiring treatment, and high cell count herds may require blanket instead of selective dry cow therapy.

- Testing. Regular individual cow cell count testing and culture & sensitivity testing is needed in herds with a high SCC. They will also require veterinary advice on how to reduce the cell count.

- Higher culling. Chronic, persistent high cell count cows may need to be replaced.

A simple cost calculator , which gives an indication of the direct and indirect costs of mastitis in a herd, based on some simple input information, is available to download. https://mastitiscontrolplan.co.uk/qpro-tools/135-simple-cost-calculator

- Milk samples: the key to mastitis control

- Taking a milk sample correctly – a visual guide for farmers

References