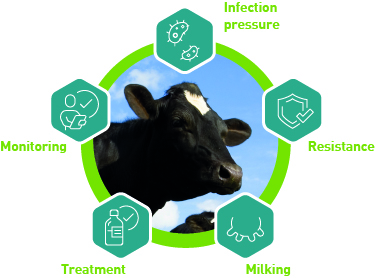

This five-point plan will guide you in your approach to tackling mastitis in a methodical way. It was developed by an international team of udder health specialists, veterinary practitioners, dairy farmers, and experts on communication and human behaviour.

The five focus areas are – in no particular order – infection pressure, resistance, milking, treatment and monitoring. They can be remembered by the memory aid ‘I Really Must Tackle Mastitis’

The five-point plan

Both clinical mastitis and subclinical mastitis are caused by bacteria entering the udder via the teat canal. Bacteria arrive at the teat canal via two pathways: from the environment of the cow (combat by reducing the infection pressure) or via the milk from another infected cow (treatment of infected cows).

The bacteria usually enter the teat canal during or shortly after milking: ensure optimal milking technology and routines.

Whether the teat infection will lead to mastitis or is successfully removed by the immune system, depends to an extent on the cow’s resistance.

To manage and control udder health, you need to measure and monitor individual cows and the whole herd.

1. Infection pressure: keep the cow’s environment clean and dry

As mentioned in the blog “Five things your farmer should know about mastitis” , clinical mastitis is mostly caused by environmental bacteria, such as E. coli and Klebsiella. Streptococcus uberis, another environmental mastitis agent, can be a major cause of high cell counts on farms.

The environmental bacteria S. uberis, E. coli and Klebsiella are often found in cow bedding. They can survive and grow there when the bedding is wet and warm: keep the cows resting places dry, by cleaning, bedding and good ventilation. Clean cow beds – whether free-stalls, cubicles, or other – are therefore priority number one. Free-stalls should be cleaned four times daily and sufficiently bedded. Klebsiella can be introduced into herds via contaminated tree bark in sawdust and wood shavings.

Manure of cows can be a major source of environmental mastitis bacteria, especially E.coli but also Klebsiella. Manure can splash up against the udder so floors must be kept as clean as possible. This also has a positive impact on foot health.

Soil can carry environmental bacteria too, which explains why we see more mastitis cases after a period of rain in herds with access to pasture. Klebsiella can also be spread via drinking water, probably ending up in the manure via the intestinal tract of the cow. Pools of water on the floor can be contaminated, as can cleaning water or cleaning towels.

The contagious or cow-to-cow bacteria, such as Streptococcus agalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus, are usually transmitted via the milk. Flies can also spread these bacteria, as can milk leakage in cubicles. Teat dips can be contaminated, too: farmers should always empty and clean the cups after each milking, and use disinfectant solutions.

Hygienic milking routines – including regular milk machine maintenance – are key, as is the early detection of cows with mastitis.

If a farm struggles with controlling udder infections, visit that farm during milking and check all possible sources of infection. Use your eyes and veterinary instincts, and take samples for bacteriological analysis.

Infection pressure can be monitored by:

- hygiene scoring the cows, starting with the udder

- hygiene scoring the beds, floors, walkways and other areas

- See article 9 “Hygiene score: measuring the infection pressure” for more details

- Use the hygiene score card in VetIMPRESS/Multi Data/Cleanliness or from AHDB at https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/cleanliness-scorecard

2. Resistance – good health for a good immune protection

Resistance comes from good health, sufficient rest, adequate nutrition and absence of stress.

The main causes for reduced resistance in dairy herds are:

- Ketosis, negative energy balance and ruminal acidosis. All these metabolic problems can arise during transition period and start of lactation. The majority of clinical cases of mastitis happens during the first month of lactation.

- Lameness: sore feet reduce feed and water intake, plus cause stress. Active lesions trigger immune reactions, using up the cow’s energy. This often goes hand-in-hand with a high infection pressure of environmental bacteria. This can sometimes make it unclear whether the dirty environment or poor foot health is the main culprit.

- Concurrent disease in the herd reduces resistance, such as Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR), Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD), Tuberculosis (TB) or parasitic infections.

- Nutritional imbalance, such as deficiencies of minerals or trace elements, or an excess (e.g. copper, selenium). Check the ration, check the feed stuffs and its nutritional analysis, but also check what the cows really eat, and perform blood tests including a liver profile. Mycotoxins can also cause resistance problems.

- Heat stress and insufficient ventilation. Heat stress is a growing problem, due to both climatic change (more warmer days) and higher milk production (more heat production by the cow).

Resistance can be monitored by:

- Scoring and observing the herd for signs of reduced resistance:

- body condition scoring: signal for ketosis and too low feed intake;

- How to score body condition

- How to score feed intake

- How to score rumen fill

- manure scoring: diarrhoea, poor digestion rate;

- How to score manure and what does it mean?

- hair coat: a dull, rough haircoat can indicate reduced resistance;

- signs of other diseases and infections: vaginal discharge, dirty noses, dirty eyes, evidence of parasites;

- wounds and lesions: foot health, hock lesions, other lesions;

- mobility scoring

- How to assess locomotion

- milk production analysis: signs of ketosis, lactation curve

- farm records of disease problems and treatments

3. Milking – help install good practices

Each cow should be milked exactly the same way during each milking, in a stress-free, peaceful environment. There should be good standard operating procedures in place for cows with abnormal milk, cows with intramammary infections, and cows under medical treatment.

Good milking requires clear and explicit protocols, to make sure that all employees are trained and know what to do. Milkers should be calm around cows, and appropriate teat dips should be used.

- The three pillars for successful milking

Milking routines should both cover the handling of normal healthy cows, and how to deal with problems. These problems can be milking issues, such as a nervous heifer or a cow that kicks off the clusters.

- What to do if things go wrong in the parlour

Milkers must also know how to handle issues such as abnormal milk, mastitis, cows with high cell counts and cows under medical treatment. They must not only know how to deal with these issues but also ensure that this does not affect the handling and milking of the other cows.

- Setting up an effective mastitis treatment plan go to: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/mastitis-in-dairy-cows

The milking machine, parlour and/or milk robot should always be in excellent working order. A maintenance contract is essential.

Key points for good milking:

– Ensure good milking routines, instruct-train-retrain all milkers, provide daily feed-back on their performance. Vets can provide protocols, and monitor, instruct and train staff;

- See The three pillars for successful milking

-Score teat end condition once a month;

- See How to score teat ends and what they mean: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/improving-dairy-cow-defences-to-environmental-mastitis-in-lactation

– Keep the milking machine clean and well maintained. Have a dynamic milking test once a year, which will help in problem solving of udder health issues.

- How, why and when to do a dynamic or ‘wet’ milking

– Ensure clear identification of infected and/or treated cows with udder infections or treatments, adequate operating procedures for abnormal milk and other issues during milking. Vets can also help and train staff in this matter.

4. Treatment – organisation is key

Treatment should be aimed at curing clinical cases of mastitis and reducing the number of infectious and high cell count cows in the herd. Key factors to be taken into account when treating are; animal health, food safety (no medicines, residues or abnormal milk in the tank) and public health (controlling antimicrobial resistance).

Farmers will look to their vets for guidance in particular for:

-treatment plans and protocols;

-instruction and training:

- how to identify cows that need treatment

- how to give treatments

Setting up an effective mastitis treatment plan: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/mastitis-in-dairy-cows

- monitoring cows that require treatment (problem cows)

- monitoring cows that have been treated (treatment result, follow up)

- proper storage and supply of treatment materials such as syringes, needles, medicines, disinfectants, gloves

How to help farmers organise a treatment area

Good udder health support is based on regular farm visits. Topics to be covered are cow and herd monitoring as well as the other four points of the five-point plan: infection pressure, resistance, milking and treatment.

Planning your monthly and yearly dairy farm visits

5. Monitoring – checks and balances

A dairy farm is a commercial business, producing milk and meat of excellent quality while respecting the farm staff, the animals and the environment. Running a business starts with goals: how much milk? What level of udder health? Monitoring helps to check if the processes are delivering the desired results.

Udder health is monitored at three levels:

1. Individual cows: identification and recording of cows at risk of, or showing evidence of, an intramammary infection. Each cow should have its own records with all relevant data regarding her udder health and general health. This will help in decision making in a case of mastitis and it allows good traceability of the quality of milk and meat sold by the farmer.

2. Bulk milk and herd metrics: data of the entire herd will provide an insight into what is happening, such as the bulk milk cell count, percentage of cows with high cell counts or percentage of new cows with high cell counts.

3. Monitoring should also give insights into the quality of the success factors (five point plan) and the risk factors, as these decide the results in the future.

These points can be monitored as follows:

Milk sample analysis gives an overview of the bacteria that cause udder infections

- Milk samples: the key to mastitis control

- Taking a milk sample correctly: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/aseptic-milk-sampling

Hygiene score gives an idea of infection pressure

- How to assess farm hygiene by looking at cows

Body condition score gives an image of energy balance during lactation;

- How to score body condition

- How to score feed intake

- How to score rumen fill

Therapy evaluation tells you how effective the treatments have been

In practice, veterinarians should co-ordinate the monitoring of udder health. Ideally, this takes the shape of a yearly meeting during which the farm goals are defined, and the role of the vet is specified.

- – Planning your monthly and yearly dairy farm visits